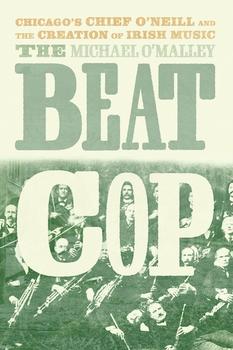

In his book, The Beat Cop: Chicago's Chief O'Neill and the Creation of Irish Music (University of Chicago Press, May 2022), George Mason University history professor Michael O’Malley recounts the life of Irish immigrant and Chicago chief of police Francis O’Neill and his influence on Irish music.

What inspired you to write this book?

O’Neill’s life was an amazing contrast between footloose freedom—he wandered the world as an itinerant sailor, he herded sheep for a while in California—and state authority. Chicago was a very violent place. As a police officer he had to stop other people from exercising certain legal and illegal freedoms. As chief of police he had to manage staff, compile statistics, issue annual reports, and handle the media. In 1900, he was on the cutting edge of modern industrial life. But then he was obsessed with folk music. There were immigrants from every county of Ireland in Chicago, and he was relentless in collecting and cataloging the tunes they played. He used his police authority to accomplish it. The combination of policing an industrial city and collecting the music of rural people was fascinating.

Was there anything in your research that surprised you?

The way Chicago operated on personal favors and cronyism. I knew this, but actually documenting it was startling. O’Neill was a talented and capable guy but was frustrated that he never got a promotion without a team of allies—alderman, judges, businessmen—who could momentarily outbid some other guy’s team. He wanted there to be a basis in merit, but the alderman’s pal got the jobs.

What is your favorite Irish song and why?

O’Neill mostly collected tunes, not songs—instrumental dance tunes with no lyrics. The tunes don’t have standard names. As a music collector, O’Neill would find the same tune with half a dozen names, or no name at all. And like a lot of folk music, Irish music is weird—both happy and sad at the same time, kind of wild feeling. My favorite might be a jig called “The Pipe on the Hob.” If I had to pick a song with lyrics, it might be “The Kerry Dances,” even though it’s very sentimental.

What are you working on now?

In 1884, the state of Virginia declared two of my ancestors—one born in Donegal, Ireland—to be Black people. I’m working on why, [as] part of a book on the relationship between genealogy and history. Millions of people find their most meaningful connection to the past through family history, and I’m exploring how the tools of genealogy have shifted over time, from local lore to government records to DNA.