In This Story

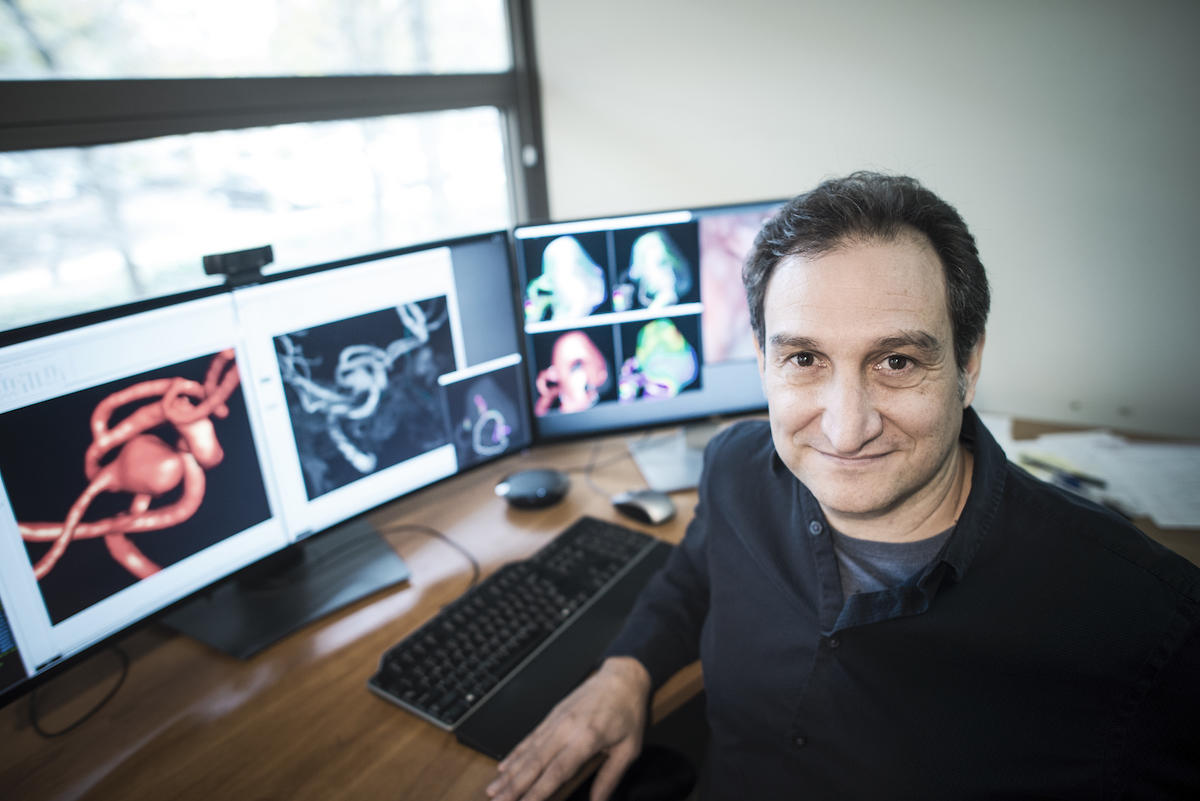

The localized enlargement of arteries in the brain, known as cerebral aneurysms, can have devastating consequences. George Mason University researcher Juan Cebral and his team are studying major risk factors for aneurysms and how to identify high-risk patients who need prompt and aggressive treatments.

This study, funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, includes clinical and research investigators from the University of Pittsburgh, Northwell Hospital in New York, Allegheny General Hospital, the University of Illinois at Chicago Medical Center, Helsinki University Hospital, Tampere University Hospital in Finland, Inova Fairfax Hospital, Jikei University, and Geneva University Hospital. These collaborators have assembled a database of approximately 3,000 aneurysms and have recently published three articles that have led to continued support from the National Institutes of Health.

Mason faculty are also working with Cebral, including Martin Slawaski from the College of Engineering and Computing, Rainald Lohner from the College of Science, and Fernado Mut from the Computational Hemodynamics Lab, which Cebral leads.

Cebral and his team are specifically focusing on aneurysms with blebs, which are secondary swellings found in weakened sections of the aneurysm walls. Tearing of the wall, or a rupture, is more likely to occur when blebs are present. These ruptures cause cerebral hemorrhages, leading to serious health complications or death.

The research team found two notable clinical characteristics among patients diagnosed with brain aneurysms: patients with blebs are more likely to have dental problems, such as periodontitis and other dental infections, and women who are undergoing hormone replacement therapy tend to have fewer blebs. They also discovered that the way the blood flows inside an aneurysm, and whether a bleb has a thick or thin wall, can help determine the condition’s severity.

“Blebs that had a strong blood flow generally had thinner walls compared to those with weak blood flows, which had thicker walls,” said Cebral, who is in the Department of Bioengineering. “The conclusion here is that not all blebs are the same: Some are more dangerous than others, and flow conditions may help us recognize which aneurysms need immediate treatment.”

Cebral is hopeful that the research findings contribute to progression in how aneurysms and blebs are currently evaluated and treated. For instance, if the association between dental problems and bleb formation continues to be proven on a larger scale, Cebral suggests that an emphasis on intense dental hygiene may be an effective way to stabilize the aneurysm and avoid invasive treatment.

“Our goal is to help identify patients who need rapid treatment and those whose diagnosis may not be as threatening,” said Cebral. “Understanding that not all aneurysms and blebs are the same is important because we should not assign the same risk level or care plans to all patients.”